What It’s Like To Visit a WW2 Concentration Camp – Our Visit to Dachau

Dachau. You’re probably thinking to yourself right now – “What the heck is Dachau?” Well, I hope after reading more below you remember or learn something you didn’t know before you came here to read this. Sometimes part of traveling is seeing history, and sometimes that history is terrible.

Dachau is a town in the German state of Bavaria which is located in the Southern part of Germany, near Munich. It also is the home to a disturbing, yet tremendous piece of history – The Dachau Concentration Camp. Opening in 1933, this was one of Adolf Hitler’s longest running concentration camps. Most people have heard of Auschwitz (in Poland), which was the largest camp, so Dachau can sometimes be overshadowed and forgotten.

I had heard of Dachau before visiting because it was covered in a Holocaust History class I took in College. To sum up the somber details, so many people (thousands upon thousands) died at this camp due to extremely poor working conditions, sickness, and experimental testing, just to name a few. Unlike Auschwitz, Dachau was not made to be an extermination camp, although they did install the gas chambers here. It is believed these gas chambers were never used for mass extermination, but were probably used for experimental testing.

Dachau is an easy half day trip from Munich via train, and something that you can do on your own. Board the S2 Peterhausen train from Munich for a ride of approximately 20 minutes to Dachau. When exiting the train station, walk across the street to the bus stop. Take bus 724 or 726 to the end of the line. When you arrive, get a map upon arrival so you know which buildings are which as you walk through. There is also an audio guide for a small fee. It is free to walk around the grounds.

The whole day set the stage for our visit, as the sky was solid gray in color, and it was lightly snowing/drizzling. Sad and depressing. It’s hard to keep somber thoughts from creeping in on how we arrived on a train that had cushioned seats and how we would also be departing this camp. During the opening of the camp, Jews coming to the camp for a permanent stay arrived like cattle in a train car with enough room to stand, and most would not be departing (let alone have any idea what was to come of them).

I expected to see the famous “Arbeit macht frei” sign upon entering the camp. I first learned of this sign/phrase by recalling that I’ve seen pictures of it printed in my grade school history class books. I was surprised to see that it was not there. This slogan translates to “Work makes you free.” So many of these people had no idea what was to become of them. I dug a little more into the door/sign missing and discovered that it was stolen. Since my visit to Dachau, the iron gates with the slogan have been found in Norway and have since been put back in place.

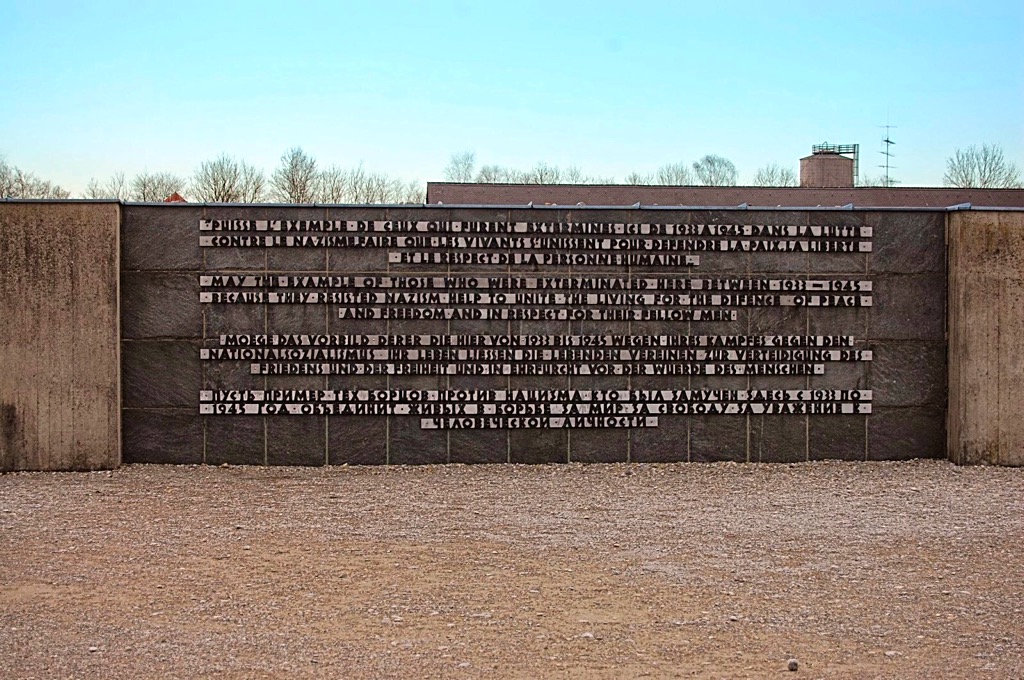

Before you squint and try to read the text on the International Memorial pictured above, here is a much easier-to-read copy of it:

“May the example of those who were exterminated here between 1933 and 1945 because they resisted Nazism help to unite the living for the defense of peace and freedom and in respect for their fellow men.” The monument was created under the assumption that the visitor would take the same path that prisoners had once walked, entering through what used to be the Jourhaus. This entrance that the prisoners were forced to use was to be the entrance that survivors would later re-enter as free people.

(From: KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau website.)

Hidden in the middle of the dark despair above, the Iron grouping in the center of the picture is the International Monument (representative of skeletons hanging from barbed wire) dedicated by an artist/former prisoner in the 1960’s as a Monument reminder – “Never Again.”

The Bunkers above, unlike the Barracks, were for the really bad prisoners – i.e. someone that might have tried to assassinate Hitler. Think of these more as “standing room only” arrangements. I mean that literally! The rooms were not even large enough for the people inside to sit down. We were told that the prisoners inside were kept there for days. After the Bunkers, we were really ready to leave. We had seen enough. It is difficult to really describe how we felt as we walked through this place. We walked around with heavy hearts and feelings of sorrow for those who endured places like this and Auschwitz; and yet we also felt grateful that we were able to see Dachau, relatively unchanged.

All in all, this was a surreal experience that most people don’t get the opportunity to do often (if ever) and something I won’t ever forget.